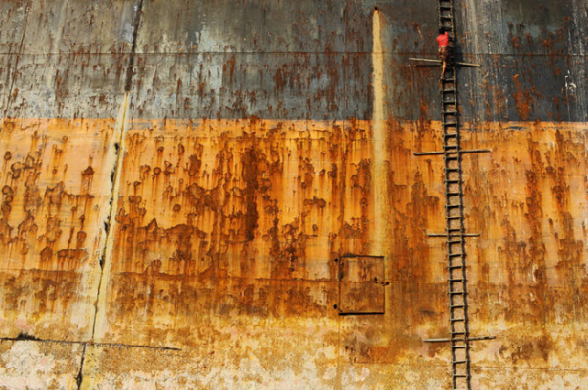

Of Ships and Men–Cameron Conaway’s Poem about the Children Who Break Ships Apart in Bangladesh

Of Ships and Men

There are ships like hotels horizontal

and there are children and children

breaking, dragging these dead vessels

through beach sand soiled with oil

through the swirling peace rainbows

of slavery, a six month deconstruction

of scrap metal and tiny little lives

scraping by one then two then twenty

broken walls of asbestos at a time

when there is no gear, no gloves

and masks only of signage bold fronted

“No Child Labour, We Take Safety First”

while Nasima, 8, of Chandan Baisha,

tries to hide just beyond the gates.

Bits of rust from the iron plates jump

into my eyes. Tomorrow? Don’t know.

We have too much work to do today.

And Sohel, 11, who came from Comilla:

My mother works at the jute mill and I

started working last year at the yards

as a cutter helper. My father never visits.

He sometimes looks for me in the streets

and tries talking to me, but I refuse.

He harmed my mother too much.

In the village, no work. Here, work.

My ambition is high. I want to become

a cutter-helper. Maybe in five years.

And Robani, 12, from Moheshkali Island

who left his village to come here after

the river took his family’s strip of land,

who watched as his father was crushed

by some falling part from the floating

dustbin, who saw his father’s shin bone

jutting white out from temple red

and who was told by the foreman

Your father was too weak for this job.

Now is your time to be the real man

of your family, a strong man that does

not break. Robani recalls not the years

when he and his father caught fish

or the time they played hours of cricket

with a bamboo bat and old compass case

but of that white and red mangle of man.

At night as he sleeps he hears orders

and he hears the hushed sound of heavy

steel ship part thump into black sand,

the sound that killed his father as if

his father had not stood between

the black steel and the blacker sand,

the weight of it all so fast that a man

can’t sound, no moan, no emotion,

bones and memories and history ground,

crumpled quietly, unlike a paper sheet

loud in crumpling and capable of reuse

or the sagor waves out beyond the black

or the thunder or of an echo which is

not even alive but an imitation, no,

his father was pestled silently unlike

the rice or flour or tea or other fined

things at the mad market. How much

to buy the silence of a man crippled?

Depends on how crippled. 10,000 taka

if one can still walk, talk, use both arms.

It’s been forty years since the first vessel.

No facts for flesh, only for things metaled:

Bangladesh is world’s largest shipbreaker.

Bangladesh is world’s first shipbreaker.

Gets 30% of steel shipbreaking.

Has thousands of jobs from shipbreaking.

But what of shipbreaking beating out

child prostitution in dangerous jobs?

Or the people, miles away from the yards,

who have for generations survived on

fish that are no longer. Their choice:

be broken by labor or by starvation.

What of how 20% of the workers

are preadolescent boys? Or the activist

who knows Chittagong needs these ships

but wants only safety and no child labor,

who says to me: You watch. When they

kill me nobody will care. One replaces

another here. The steel of these beasts

has shaped more than our men’s bodies.

*******************************

Cameron Conaway is the Social Justice Editor at The Good Men Project.

He may be followed on Twitter by going here.