CHILD LABOR AND ENSLAVEMENT IN GHANA’S LAKE VOLTA FISHING INDUSTRY

By Sharon L. Fawcett, CLC Intern

For a small sum of money, James Kofi Annan’s father handed him over to a child trafficker when he was just six years old. Born into a family in Ghana with 12 children, there was no money for school uniforms and books. So instead of gaining an academic education, James would learn the painful lessons of the enslaved, in Ghana’s fishing villages.

Sold by his trafficker to a Lake Volta fisherman, James worked 17 hours per day, enduring constant physical and emotional abuse. When displeased, his master often withheld food, beat him with a paddle, or threw him in the lake.

Lake Volta, one of the world’s largest man-made lakes, was created by the construction of Ghana’s Askombo dam in the 1960s. Although the lake provided a bountiful supply of fish for many years, fish stocks have been declining in recent years, making it more difficult for fishermen to earn a living. Children provide a cheap source of labor and their tiny fingers prove useful for picking the fish that are captured in the nets’ webbing, as the holes get increasingly smaller to catch smaller fish.

The children trafficked to work in Ghana’s fishing industry as bonded laborers are as young as four years of age. Their tasks may include paddling boats, hauling nets, or performing domestic labor in the homes of fishermen. Like James Kofi Annan, these children work long hours for no pay; do not attend school; and are often malnourished, sleep deprived, and treated abusively. Nets often get snagged on submerged tree branches and children forced to dive underwater to free them risk water-borne diseases and drowning.

According to the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the International Labor Organization (ILO), 60 percent of the world’s 215 million child laborers work in the agricultural sector—comprising activities in agriculture, livestock-raising, forestry, and fishing. In Ghana, one in six children aged six to 14 are involved in child labor. Eighty-eight percent of them work on farms; another 2.3 percent in fishing.

Work that is likely to harm the health, safety, or morals of children is categorized as hazardous by the ILO. This is the kind of work Lake Volta’s child fishers are exposed to, among the “worst forms of child labor.”

Ghana has ratified several international conventions that establish standards to protect children from exploitative work, including the ILO’s Minimum Age Convention (C138) and the Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention (C182). It also has national laws restricting child labor, but the laws are not vigorously enforced. The minimum age for work in Ghana is 15 years; 18 years for hazardous work. However, the practice of children working is commonly accepted in Ghanaian society.

While education is compulsory and free in Ghana, the fees for uniforms and books provide a barrier for many families in Ghana’s agricultural communities and education is not necessarily considered more beneficial for children than work and learning a trade is. A 2013 World Bank study found that among Ghanaian household heads who are self-employed in agriculture, those with no schooling earn as much as those who have finished 9 years of basic education.

Poverty, views on education, and social customs combine to make rural families vulnerable to traffickers or fishermen who come with promises to provide children with opportunities to learn a trade and receive payment when the “training” period ends.

In 2010, the Government of Ghana took measures to tackle the exploitation of children by adopting a National Plan of Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor in Ghana. The plan provides a framework for a significant reduction of the worst forms of child labor in the nation by 2015.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) works to rescue children trafficked into Lake Volta’s fishing industry. Since 2002, more than 700 children have been liberated, rehabilitated, and reintegrated into their home communities by the IOM. Part of the reintegration process includes enrolling children in schools or apprenticeship programs and monitoring their progress, as well as offering parents “livelihood assistance training” to help them support their families. The IOM undertakes community outreach programs to prevent child trafficking in vulnerable regions, and to identify and assist existing trafficking victims. It also intervenes with traffickers, teaching them that children should not be separated from their parents or perform adults’ work.

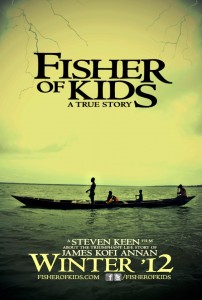

A number of non-governmental organizations perform similar work. One is Challenging Heights—devoted to liberating, educating, and rehabilitating enslaved children. Established in 2003, Challenging Heights liberated 500 children in its first four years alone. Its founder, James Kofi Annan, the child we met at the beginning of this piece, escaped from his master after seven years of enslavement, taught himself to read and write, went on to college, and built a successful career as a bank manager. In 2007, he gave it all up to devote himself full-time to his work as an anti-slavery activist. Winner of the 2008 Frederick Douglass Award, sponsored by Free the Slaves, and nominated for the 2013 World’s Children’s Prize, Annan and his life are featured in the film aptly titled, “Fisher of Kids.”

On World Day Against Child Labor 2013, the Child Labor Coalition was honored to host the U.S. premiere of “Fisher of Kids.”